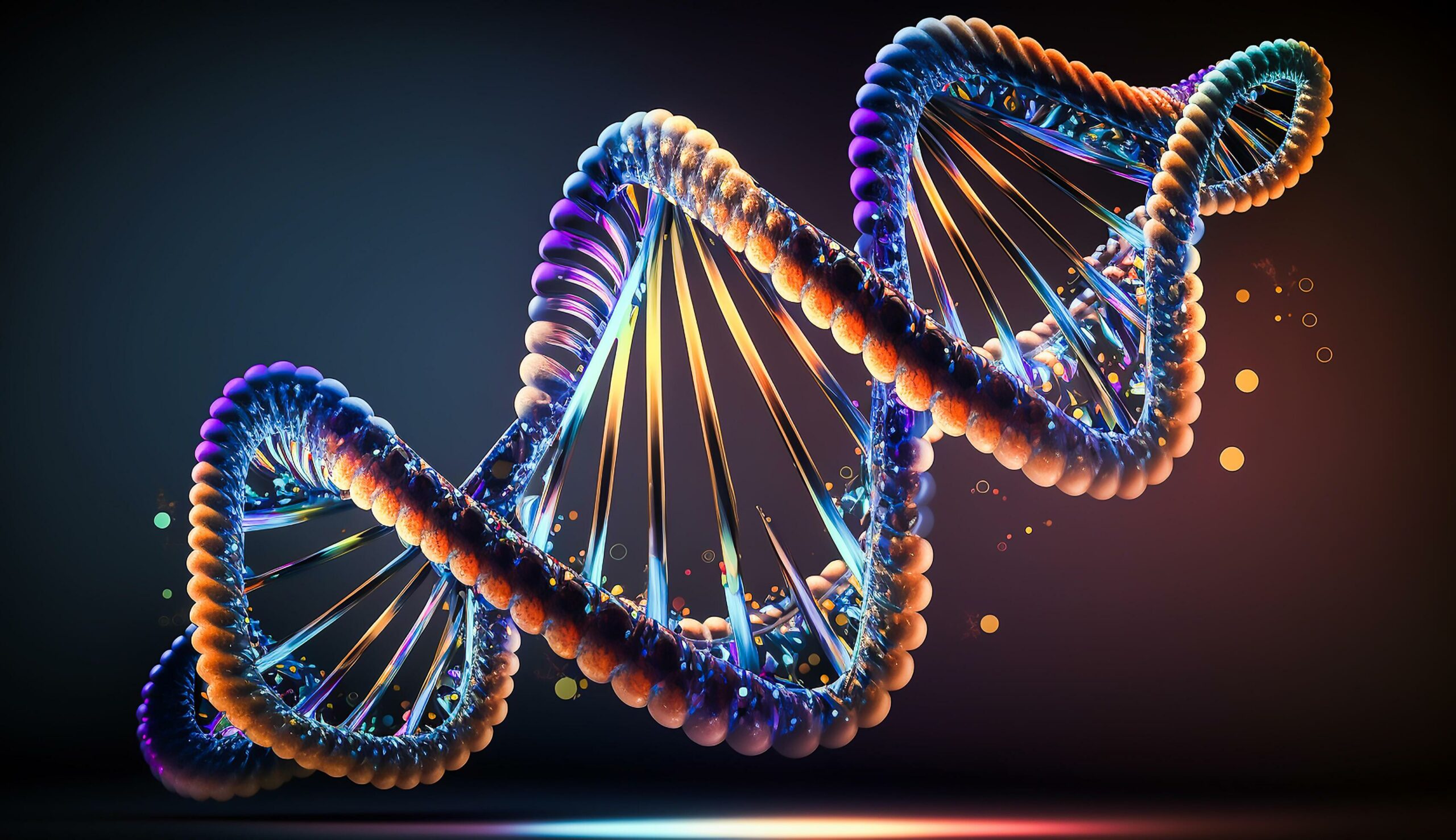

Throughout the ages, humanity has endeavored to unravel the enigma of life at its most fundamental level. Our understanding of the living organism has often been framed through the lens of biology, specifically the molecular biology of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). However, emerging research has brought to light an intriguing paradigm shift: viewing DNA not merely as the genetic blueprint of life, but as a semiconductor. This perspective opens a plethora of opportunities that could reshape our understanding of biological processes and their potential applications in technology.

To comprehend this concept, it becomes paramount to delineate the characteristics inherent in semiconductors. Semiconductors are materials with electrical conductivity between that of conductors and insulators, making them integral to modern electronic devices. They exhibit the remarkable ability to control electrical current, a property that can be finely tuned by the introduction of impurities, known as doping. This unique behavior is attributable to their atomic structure and the mobility of charge carriers within their lattice framework. Interestingly, DNA exhibits analogous properties, allowing it to modulate electronic signals under certain conditions.

The structural composition of DNA, consisting of a double helix formed by nucleotide pairs, creates a complex architecture that has remained largely unexplored in the context of electronic functionality. Current research indicates that DNA, particularly its phosphate backbone, is capable of conducting charge. This means that DNA strands can potentially facilitate electron flow, akin to semiconductor materials like silicon. Such a finding prompts a multitude of questions about the role of DNA in cellular processes and its capacity for signal transduction.

Consider the intricate processes of cellular communication and metabolic control. At the cellular level, signaling pathways depend on the transfer of information through a series of biochemical events. If DNA can indeed function as a semiconductor, one could hypothesize that it plays a critical role not only in information storage but also in information transmission. This duality introduces a fascinating dimension to our understanding of genetic expression and regulation. The ability to influence electronic properties could enhance the cellular response to environmental stimuli, suggesting a deeper integration of biological and electrical systems.

Moreover, the implications of DNA’s semiconductive properties extend into the realm of biotechnology. A notable application is the burgeoning field of bio-sensors. Traditional bio-sensing technologies often rely on metal nanostructures or conductive polymers to detect biological markers. However, the utilization of DNA as a semiconductor offers a biocompatible and environmentally friendly alternative. By constructing bio-sensor devices based on DNA strands, researchers have the potential to create highly sensitive and selective platforms for the detection of pathogens, biomarkers, or environmental pollutants—capabilities that could revolutionize diagnostics across various fields, including medicine and environmental science.

In addition to bio-sensing applications, the notion of DNA-based electronics has garnered significant interest. Researchers are investigating DNA origami, a technique that allows for the precise engineering of nanostructures using DNA molecules. These programmable constructs can be designed to execute specific functions with remarkable precision. Integrating DNA with electronic components could result in innovative memory devices or circuits that outperform conventional silicon-based systems in terms of functionality and efficiency. The possibilities of harnessing the information-processing potential of DNA evoke a sense of curiosity, particularly as we inch closer to realizing molecular computing.

Despite the promising avenues of research, critical challenges remain. The inherent stability of DNA under varying environmental conditions poses a significant barrier to its practical application in electronic systems. Furthermore, the scalability of DNA synthesis and assembly techniques must be addressed to enable widespread adoption. Nonetheless, the allure of tapping into nature’s intricate designs to create novel electronic devices cannot be overstated. A paradigm shift towards embracing DNA as a fundamental component of electronic technology is necessitating a reevaluation of existing methodologies and practices in both biology and materials science.

As we embark on this journey to intertwine the realms of biotechnology and electronics, it is imperative to delve deeper into the mechanisms underlying DNA’s semiconductive capabilities. Exploring the interactions of charge carriers within DNA structures may illuminate pathways for creating hybrid systems that blend biological components with synthetic materials. Such interdisciplinary endeavors can facilitate the development of sophisticated devices capable of performing complex tasks, akin to the adaptive functionalities of living organisms.

Ultimately, the conceptualization of DNA as a semiconductor not only invigorates ongoing research but also galvanizes public interest in genetic sciences and technology. This intersection of biology and electronics fosters a community of interdisciplinary thinkers who are poised to redefine our understanding of the building blocks of life. Through collaborative efforts, the mysteries of DNA may be unraveled, leading to innovations that seamlessly integrate biological systems with electronic applications.

In conclusion, recognizing DNA as a semiconductor provides a tantalizing glimpse into the future of technology and biology. It challenges us to reconsider preconceived notions and encourages exploration into the uncharted territories of molecular electronics. As investigations proceed, one can only speculate about the transformative potential this innovative perspective holds for both scientific inquiry and technological advancement.