The question of whether doctors become ineffective in the absence of medical laboratories and radiological capabilities invites both skepticism and intrigue. Can we consider physicians to be mere facilitators of diagnostic technology, or do they possess an intrinsic value that transcends the capabilities offered by modern medical equipment? These queries encapsulate an ongoing challenge within the medical community, positing a philosophical dilemma against an empirical backdrop: are doctors, in essence, reduced to mere technicians without the vital apparatus of diagnostics?

To start, it is paramount to recognize the historical context in which doctors have operated. Prior to the advent of advanced medical technology, diagnostic tools were rudimentary at best. Physicians relied heavily on clinical acumen, intuition, and the foundational principles of medical practice—those of observation, history-taking, and the physical examination. In essence, these practitioners acted as detectives; the nuances of a patient’s presentation often elucidated underlying conditions without recourse to the sophisticated testing that we routinely employ today.

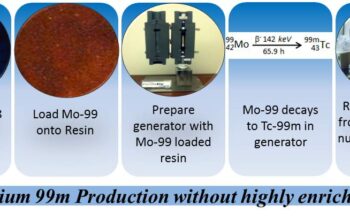

As we traverse into contemporary medical practice, however, the reliance on medical labs and radiology has burgeoned. Diagnostic imaging—be it magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), or ultrasounds—coupled with laboratory tests, has undoubtedly revolutionized the field. The immediacy and accuracy of these technologies provide physicians with insights that significantly augment their diagnostic capabilities. But therein lies the crux of the conundrum: does this increase in diagnostic precision undermine the fundamental role of the physician?

The art of medicine encompasses more than just the interpretation of test results. A physician’s skill set extends beyond bloodwork and radiographs. The ability to synthesize information, interpret nuanced patient narratives, and incorporate psychosocial contexts into care is an integral facet of their responsibilities. The most astute physicians often exhibit a comprehensive understanding of patient history, which can sometimes lead to correct diagnoses even in the absence of diagnostic machinery.

Further compelling this argument is the notion of clinical judgment. Medical training equips physicians with the tools needed to evaluate and make decisions based on incomplete information. This intrinsic capability is paramount; ailments such as complicated migraines may present indistinctly, demanding nuanced clinical acumen to distinguish them from serious conditions like a brain tumor. It raises an intriguing question: in scenarios devoid of immediate diagnostic support, can intuitive medical reasoning triumph?

Moreover, let’s consider the limitations and potential pitfalls of over-reliance on technology. An abundant availability of biomedical data does not always correlate with improved patient outcomes. Diagnostic tests can yield false positives or negatives, leading to unnecessary interventions or missed opportunities for critical diagnoses. While laboratories and imaging centers provide valuable information, they can inadvertently detract from the physician’s evaluative skills. Herein emerges the challenge: how do we navigate the delicate balance between embracing innovation and preserving the essence of traditional medical practice?

In addition, the biopsychosocial model of health emphasizes the multifaceted nature of wellbeing. It is not merely biological or physiological aspects that necessitate attention; psychosocial factors also wield considerable influence. Physicians, albeit without the immediate comforts of advanced medical technology, are adept at fostering therapeutic relationships. The act of listening, the assurance of empathy, and the creation of a trustful environment can catalyze positive health outcomes that are inherently human, sometimes eclipsing the efficacy of high-tech diagnostics.

Nevertheless, it is equally essential to address the symbiotic relationship between physicians and the diagnostic tools at their disposal. The evolution of medical practice has ushered in sophisticated instruments that serve to enhance, rather than diminish, the physician’s role. Medical laboratories perform extensive analyses that save time and labor, allowing healthcare professionals to pivot their focus toward patient interaction and comprehensive care. Likewise, radiological imaging facilitates a more intricate understanding of pathologies that may otherwise be obscure to a clinician’s eye.

To further explore the interplay between technology and human expertise, consider the role of a radiologist. This specialized physician interprets images, deducing important information that significantly influences treatment trajectories. Their work, while highly reliant on technology, still necessitates a keen understanding of bodily systems, as well as clinical knowledge, to provide meaningful insights. In this regard, the relationship remains collaborative; neither party is rendered ‘useless’ without the other, as both physicians and diagnostic tools contribute uniquely to healthcare delivery.

Ultimately, the question of whether physicians are ineffective without the support of a medical lab and radiology leads us to a broader discussion: can we fully separate the domain of medical expertise from the innovative technologies that enhance it? In a landscape increasingly shaped by diagnostics, the essential qualities of physicians—compassion, analytical prowess, and clinical reasoning—remain irreplaceable. A robust medical framework thrives not simply on technology, but on the indelible connection between provider and patient.

As we contemplate the future of medicine, it bears emphasis that training the doctor of tomorrow necessitates a dual focus: technological literacy alongside time-honored clinical skills. The essence of healthcare should hinge on the premise that technology serves as a tool rather than a crutch, and that the soul of medicine—rooted in human experience—endures as the cornerstone of effective practice. Thus, the playful inquiry of whether doctors are ‘useless’ devoid of modern diagnostics leads us to an illuminating realization: they are, and should always remain, indispensable custodians of patient care, regardless of the tools at their disposal.