In the complex realm of theoretical physics, a provocative inquiry arises: “Is it true that particles are fake?” This question, entwined in layers of abstraction and empirical evidence, can catalyze a profound shift in our understanding of reality. To embark on this intellectual expedition, one must first disentangle the concepts of “particles” and their representation in the scientific community.

Particles, as posited by the standard model of particle physics, are the fundamental building blocks of our universe. They include quarks, leptons, bosons, and others, each category fulfilling distinct roles in the cosmic symphony. These entities, however, reside not in a simplistic, tangible manner but within a framework of probabilities and wave functions. This leads to the paramount question concerning their existential validity—are particles indeed tangible entities, or could they be construed as mere artifacts of human conception?

At the heart of this inquiry lies the notion of quantum mechanics. Developed in the early 20th century, it unveiled a surreal world operating under principles that often defy classical intuition. Unlike macroscopic objects, particles exist in superpositions, wherein they can simultaneously occupy multiple states until measured. This phenomenon leaves scientists pondering whether particles are inherently ‘real,’ or if they merely serve as convenient representations of complex interactions in a probabilistic matrix.

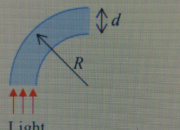

Consider the famous double-slit experiment, which showcases the duality of light and matter. When particles, such as electrons, traverse two slits, they create an interference pattern that suggests wave-like behavior. Yet, upon measurement, they exhibit particle-like characteristics. This duality raises an intriguing proposition: perhaps particles, in their essence, elude a straightforward classification as either “real” or “fake.” They are manifestations of underlying processes rather than standalone objects.

Furthermore, the perspective of particles being “fake” finds substantial backing in the realm of field theory. According to this paradigm, particles emerge as excitations in underlying fields that pervade the universe. For instance, the Higgs boson, celebrated for its role in endowing mass to other particles, is fundamentally an excitation of the Higgs field. This realization compels a reconsideration of the nature of particles; they may not exist independently but rather as ephemeral fluctuations in a vast, interconnected fabric of reality.

Moreover, the implications of considering particles as non-fundamental challenges conventional notions of existence and reality. It calls to mind philosophical discourses on idealism and realism—two schools that wrestle with the nature of what constitutes reality. If particles are indeed grounded in quantum fields, then the universe may be more accurately depicted as a dynamic interplay of fields rather than a mere collection of discrete entities. Thus, particles could be perceived as merely conceptual tools rather than definitive constituents of the cosmos.

This leads us to the question of measurement and observation in quantum physics. The act of measurement seemingly collapses wave functions, leading particles to adopt specific states. This observer effect introduces peculiar considerations about reality itself. Are particles genuine independent entities, or are they contingent upon the act of observation? Herein lies a tantalizing possibility: reality might not be a static tapestry woven from particles but instead a malleable construct forever altered by conscious interaction.

To add depth to this narrative, one must also reflect on the ontological implications stemming from theoretical constructs such as string theory. This hypothesis posits that what we refer to as particles are, in fact, one-dimensional strings vibrating at different frequencies. The various vibrational modes yield different particles, thus reinforcing the proposition that particles are not fundamental but derived entities. String theory pushes the boundaries of conventional understanding and evokes the notion that particles, as we delineate them, could be illusory representations shaped by theoretical abstractions.

Yet, amidst the explorations surrounding the authenticity of particles, empirical evidence remains a cornerstone of scientific validation. Particle accelerators, such as the Large Hadron Collider, continuously challenge physicists’ comprehension of the fundamental nature of matter. The discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, substantiated through rigorous experimentation, provided a tangible acknowledgment that while our conceptualizations may fluctuate, the manifestations yield testable, repeatable results within the confines of our current models.

The discourse does not conclude. The question of whether particles are fake transcends a mere yes or no dichotomy. It invites contemplation on the very nature of reality, perception, and existence. Acknowledging particles as constructs within vast and intricate frameworks does not diminish their significance; instead, it uproots the complacency with which humanity has embraced traditional notions of materiality. Thus, the journey shifts from a simplistic endorsement of particles toward a more nuanced acknowledgement of reality’s complexities.

In conclusion, as we grapple with the profound question of whether particles can be deemed “fake,” we unearth a rich soil for intellectual fertilizer. This inquiry does not seek to discredit the existence of particles but rather to expand our horizons regarding how we conceptualize and interpret the universe. By embracing a more abstract perspective, we unlock doors to new realms of understanding—ones that challenge our ontological assumptions and push the boundaries of scientific inquiry, propelling us toward a deeper comprehension of existence itself.