Throughout history, the concept of nuclear weapons has captured the imagination of the public. From the chilling ramifications of the bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the global discourse surrounding nuclear proliferation, the topic invokes a complex tapestry of scientific, ethical, and political considerations. The question emerges: is it possible to construct a nuclear bomb using everyday items? This inquiry is not merely academic but is imbued with implications that resonate through societal fears, technological accessibility, and the ethics of knowledge dissemination.

At first glance, the notion that commonplace materials could be utilized to create a weapon of mass destruction seems preposterous. However, it taps into a broader fascination with the extraordinary potential of ordinary objects. Items that are routinely found in households may yield surprising applications in various scientific domains, leading to a misperception that they could assemble into something inherently dangerous. To explore this issue, one must delve into the fundamental principles governing nuclear reactions and the materials required for such processes.

Nuclear bombs derive their destructive power from two primary physical processes: fission and fusion. Fission, the splitting of atomic nuclei, is the basis for most nuclear weapons. Elements like uranium-235 and plutonium-239 are pivotal to this process, as they possess the requisite characteristics to sustain a rapid chain reaction leading to a massive release of energy. Conversely, fusion, which involves the amalgamation of light atomic nuclei, powers hydrogen bombs, releasing even greater energy but requiring extreme conditions to initiate.

The synthesis of these elements is not achievable with everyday items. Naturally occurring uranium is present in low concentrations and requires considerable refinement and enrichment to obtain the fissile isotope necessary for a nuclear bomb. In contrast, plutonium is not an element found in the natural world in significant quantities and is typically produced in nuclear reactors. This presents the initial barrier: the materials requisite for nuclear weaponry are neither commonplace nor easily accessible.

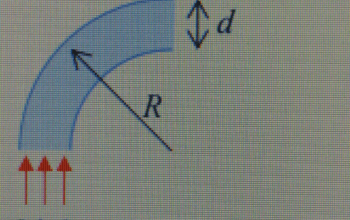

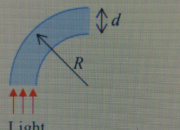

Moreover, the actual engineering of a nuclear bomb is an intricate endeavor that necessitates advanced knowledge of physics, engineering, and sophisticated technologies. The design of a nuclear weapon involves the construction of intricate mechanisms that orchestrate the precise conditions necessary for a successful detonation. Concepts such as critical mass, inertial confinement, and nuclear yield require a depth of understanding that transcends layperson knowledge. These complexities serve as a deterrent against the notion that everyday items can be whimsically combined to fashion a nuclear device.

Another critical aspect is the legal and ethical ramifications surrounding nuclear proliferation. The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), established in 1968, is a cornerstone of international law aimed at preventing the spread of nuclear weapons and fostering disarmament. Under this treaty, nations are mandated to forgo the development and acquisition of nuclear arsenals, reinforcing the notion that the possession and creation of nuclear materials should be heavily regulated and monitored.

This legal framework reflects a societal consensus that a nuclear-armed world poses existential risks. The fascination with the possibility of constructing such weaponry from quotidian materials often stems from broader fears around terrorism and rogue states. With numerous countries possessing nuclear capabilities, the specter of nuclear weapons falling into the hands of non-state actors exacerbates the anxiety surrounding their proliferation. These fears are compounded by sensationalized media portrayals, contributing to the misguided notion that a “dirty bomb” or improvised nuclear device could be produced from innocuous household items.

In examining the technological landscape, one finds advancements that, while impressive, do not necessarily lead to the democratization of nuclear weapons creation. The proliferation of information through the internet and the increasing accessibility of sophisticated technologies such as 3D printing have led to debates regarding the implications for national and global security. However, despite these advancements, the barriers to successfully creating a nuclear bomb remain formidable, encompassing regulatory, technological, and practical concerns.

Furthermore, the ethical implications of knowledge associated with nuclear technology cannot be overstated. Scientists and engineers are acutely aware of the potential misuse of their work and have traditionally adhered to principles that prioritize the welfare of humanity. The existence of stringent security measures and the accountability of professionals involved in nuclear physics serve to prevent the misuse of knowledge and to safeguard against catastrophes. This moral thread weaves through the inquiry into nuclear weapon construction, emphasizing the collective responsibility of society to ensure that scientific advancements do not culminate in calamity.

In conclusion, while the allure of creating a nuclear bomb from everyday items may intrigue some, it remains a fundamentally unattainable goal due to the complex interplay of physical, technological, and ethical barriers. The discussion surrounding this issue highlights deeper societal fears and examines the vast ramifications of nuclear proliferation. Ultimately, the fascination with nuclear weapons underscores humanity’s relentless pursuit of knowledge, tempered by the responsibility to wield such power with caution and foresight. It is this duality of wonder and wariness that characterizes the dialogue surrounding nuclear technology and its potential implications for civilization.