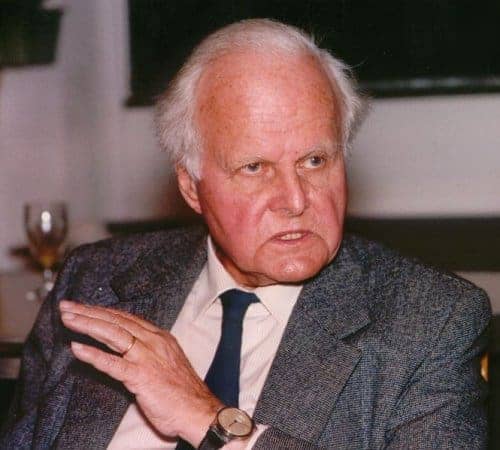

In the panorama of 20th-century physics, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker stands as a formidable monument, a rare confluence of intellect, philosophy, and humanitarian spirit. A figure woven into the very fabric of modern scientific thought, his contributions span disciplines, from nuclear physics to philosophy of science, encapsulating a life poised delicately at the intersection of empirical inquiry and ethical contemplation. His journey, from a prodigious young scientist to a sage elder within the academic community, yields a tapestry of insights and challenges that continue to resonate today.

Born on June 28, 1912, in Kiel, Germany, von Weizsäcker navigated the complexities of an intellectually charged environment. His father, a prominent physicist, and his mother, a pianist, instilled in him an early appreciation for science and the arts—a duality that would characterize his multifaceted career. As a young man, he exhibited prodigious talent, quickly ascending the academic ranks. During his formative years, he studied under luminaries such as Werner Heisenberg and became enmeshed in the vibrant discourse surrounding quantum mechanics.

Von Weizsäcker’s intellect crystallized during his role in the German nuclear weapon project during World War II. While many scientists were consumed by the allure of technological progress, he grappled profoundly with the ethical implications of his work. To him, the discovery of nuclear fission was not merely a scientific triumph but a double-edged sword, symbolizing humanity’s ascent into a realm replete with perilous potential. This internal conflict gave rise to his pivotal 1945 essay, “The Unity of Nature,” where he articulated a vision of science as a poignant narrative that should harmonize with ethical responsibility.

The metaphorical thread of his life can be likened to a river—initially drawn into the currents of scientific fervor, yet perpetually seeking deeper tributaries of meaning. In post-war Germany, von Weizsäcker emerged not only as a scientist but also as a public philosopher. His reflections on the role of science in society heralded a crucial shift in discourse, transitioning from technical discourse to a deeper consideration of the moral responsibilities inherent in scientific endeavors. Here, he pioneered the integration of philosophy into the fabric of scientific thought, inviting both scientists and laypersons alike to contemplate the implications of their pursuits.

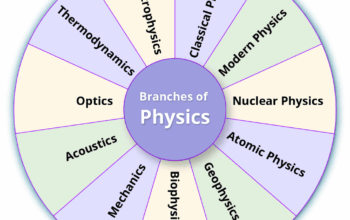

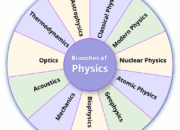

His significant contributions to theoretical physics are indeed noteworthy, particularly his formulation of the liquid drop model of the atomic nucleus. This model offered a compelling framework for understanding nuclear interactions and laid the groundwork for advancements in nuclear physics. Yet, von Weizsäcker’s impact transcends his scientific achievements. He ventured into the realm of environmental and philosophical discussions, positing that the threats posed by nuclear technology demand a concerted ethical approach. He emphasized the importance of sustainability—an argument that resonates resoundingly in present-day discourse about climate change and technological stewardship.

As the decades unfolded, von Weizsäcker’s legacy continued to evolve. In the 1950s, he ventured into the interdisciplinary territory, engaging with sociologists, economists, and ecologists. His landmark work, “The Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy,” highlights the dichotomy between scientific innovation and societal obligation. In this context, he posited that knowledge must serve the greater good, framing humanity’s understanding of science as a collective venture rather than an isolated intellectual endeavor. His vision was one of illumination—wherein science shines a light not only upon the unknown but also illuminates the moral pathways of its application.

In later years, von Weizsäcker turned his attention to the philosophies of science and knowledge production. He interrogated the very foundations of scientific inquiry, advocating for a holistic approach to understanding the universe. His notion that scientific knowledge must account for human experience resonates deeply in contemporary discussions regarding the philosophy of science. Here, he posited that the quest for understanding is itself a philosophical endeavor, urging scientists to recognize the limitations of their methodologies and the broader implications of their findings.

Von Weizsäcker’s unwavering commitment to ethical inquiry was encapsulated in his assertion that “science without conscience is a soul without the body.” This ethos prompted dialogues that transcended disciplinary boundaries, affecting not only the scientific community but also policymakers and educators. He became an advocate for integrating ethical considerations within scientific education, thus preparing future generations of scientists to navigate the moral labyrinth that accompanies technological advancement.

His latter years were devoted to academia and public discourse, where he remained an influential figure until his passing in 2007. By then, he had cultivated a legacy that bore testimony to the profound impact one individual can have on both the scientific and philosophical landscapes. His life, much like a complex symphony, harmonized the dissonance between scientific ambition and ethical responsibility.

In a world increasingly faced with the dichotomy of astonishing technological advances and dire ethical ramifications, the reflections and teachings of Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker remain eerily prescient. His life urges us to transcend the parochial confines of traditional fields of inquiry, advocating for a synthesis of knowledge that embraces both empirical evidence and moral contemplation. In commemorating his contributions, we not only honor a remarkable physicist and philosopher but also affirm our collective responsibility to uphold the ideals of integrity, foresight, and humanitarianism in our ever-evolving scientific landscape.