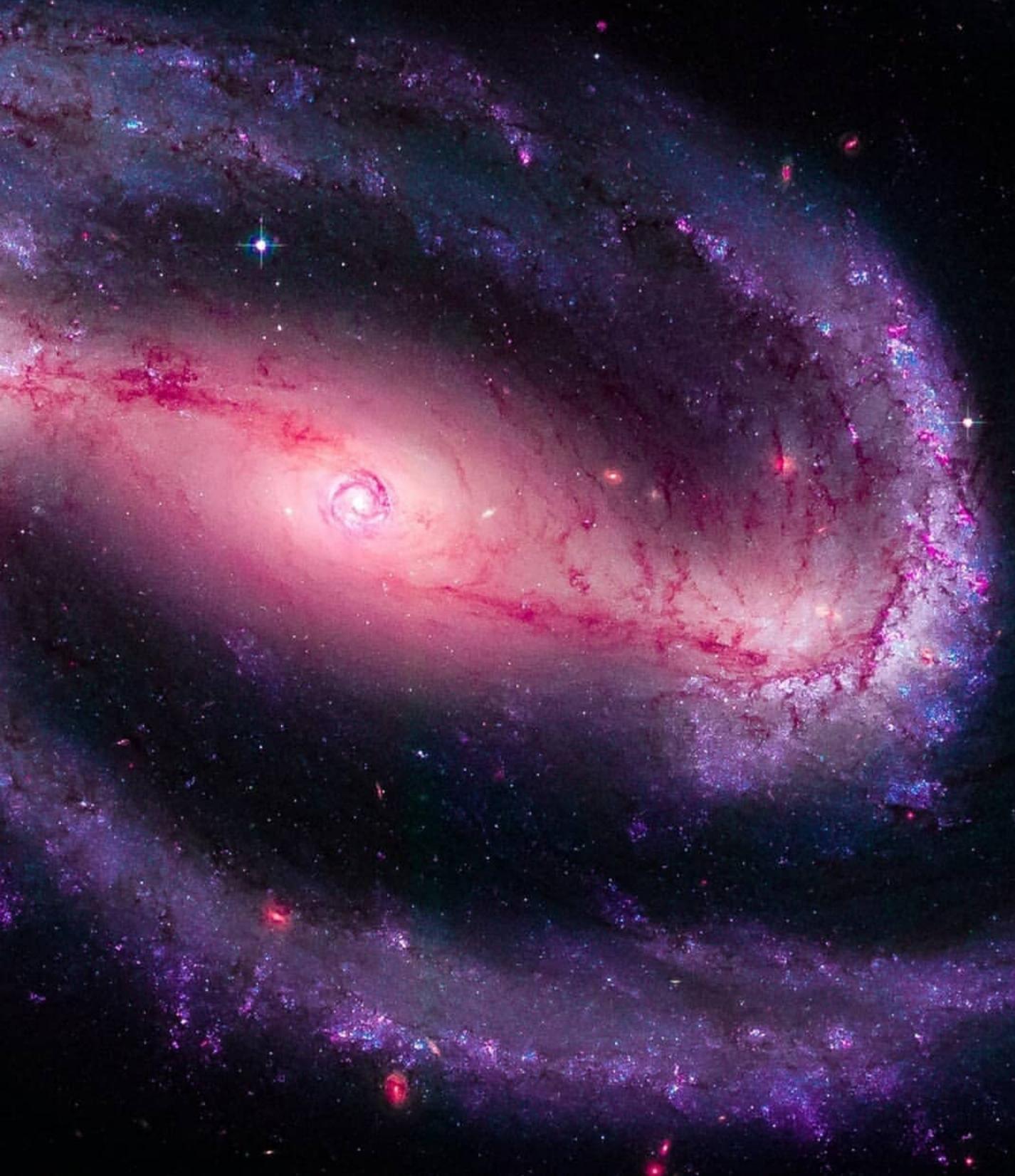

The universe is an unfathomable expanse, teeming with celestial phenomena that challenge our understanding of astrophysics. Among the myriad mysteries it presents, one particularly awe-inspiring concept is that of galactic wanderers—exoplanets found orbiting stars that lie beyond our Milky Way galaxy. While our own stellar neighborhood has yielded an abundance of exoplanetary discoveries, the notion of unanchored planets existing in distant galaxies propels the imagination into realms previously reserved for speculative fiction.

Can exoplanets survive the harsh cosmic environments of extragalactic stars? This question invokes wonder and skepticism alike, as well as a plethora of scientific challenges related to the detection, characterization, and theoretical modeling of these elusive worlds. To engage with this idea, one must contemplate several interrelated factors that govern the interplay between stars, planets, and the expansive void of intergalactic space.

Notably, the very first challenge lies in the fundamental difficulty of observing extragalactic stars. Our current astronomical instruments, such as the Hubble Space Telescope and the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, are finely tuned to explore the local universe, primarily focusing on the Milky Way and its immediate neighbors. Detecting stars located millions, if not billions, of light-years away presents an almost insurmountable challenge due to the vast distances involved. The faint light emitted by a distant star may easily become indistinguishable from that of the cosmic background radiation, making direct observations of such stellar bodies elusive at best.

One must consider the methods of detection that could aid in identifying exoplanets around extragalactic stars. Gravitational microlensing—a phenomenon where a massive object, such as a star, bends the light of a more distant background source—could be a promising avenue. This technique exploits the warping of spacetime as predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity, providing an indirect means of detecting planets that might not otherwise be observable. By surveying regions of space where gravitational lenses are more prevalent, astronomers could glean insights into the characteristics and orbital dynamics of suspected exoplanets.

Moreover, the gravitational stability of exoplanets in an extragalactic context raises critical questions. Planets orbiting stars in our galaxy are influenced by the gravitational forces of nearby celestial entities, which contributes to their overall stability. However, in the chaotic environment of an extragalactic galaxy—with its unique gravitational interactions, supermassive black holes, and the presence of tidal forces—one could speculate whether planets could maintain stable orbits around their parent stars. Understanding these dynamics necessitates advanced astrophysical modeling on cosmic scales, integrating elements of celestial mechanics, star formation theories, and the characteristics of intergalactic environments.

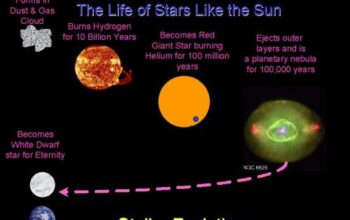

Yet, even if distant planets can exist in a stable configuration, their compositions and atmospheres may be fundamentally different from their counterparts in the Milky Way. The elemental makeup of stars and their surrounding protoplanetary disks dictates the types of planets that can form; thus, the composition of stars in extragalactic realms could invariably lead to the emergence of distinct planetary types. For instance, the disparity in metallicity—the abundance of elements heavier than helium—between galaxies could produce rocky planets or gas giants with unique physical and chemical properties. What implications would the variability in planetary systems have for our understanding of life? Could fettered opportunities for genesis arise within these alien worlds?

Furthermore, the concept of habitability extends beyond mere physical presence. Investigating whether exoplanets in other galaxies possess the necessary conditions to harbor life introduces an additional layer of complexity. Water, often referred to as the elixir of life, must remain liquid under a planet’s atmospheric and geological conditions. The potential diversity of climates across different exoplanetary systems would necessitate novel criteria for habitability—criteria that may be utterly alien compared to environments found within the solar system.

Furthermore, intergalactic migration of exoplanets through gravitational interactions and encounters with rogue stars holds intriguing implications. Could ejected planets find themselves adrift between galaxies? If so, could these solitary wanderers eventually become hosts to life? The statistical probabilities of such phenomena occurring warrant rigorous investigation, as they could expand our understanding of planetary genesis under extraordinary conditions.

The exploration of exoplanets outside our galaxy illuminates the vast unknowns surrounding planetary formation and evolution. Furthermore, it inspires a reevaluation of current dogmas in planetary science. If worlds harboring life can exist beyond our cosmic backyard, what does that mean for our quest to comprehend the parameters that govern life’s emergence universally? As researchers venture into the tumultuous territories of extragalactic astrology, they must reconcile theories, refine methodologies, and fuel creative hypothesizing.

In conclusion, while the concept of galactic wanderers excites our intellectual curiosity, it also propounds formidable challenges that reside at the interface of modern astrophysics and planetary science. Observational limitations, gravitational instabilities, compositional variability, and the quest for habitability coalesce into a complex tapestry of inquiry. As exploration intensifies, the pursuit of exoplanets orbiting extragalactic stars may unveil truths that redefine our understanding of existence itself, bridging the chasm between the known and the mystical, and propelling humanity deeper into the cosmic abyss.