The intricate world of nuclear weaponry has long captivated the intellectual curiosity of scientists, policymakers, and the general public alike. The primary question that arises is whether nuclear weapons can ‘go bad,’ thereby losing their reliability and safety as instruments of deterrence. This inquiry invites a plethora of considerations, from the chemical and physical properties of the materials involved to the geopolitical ramifications of failing arsenals. Thus, let us explore the multifaceted dimensions of this subject.

At the crux of the matter lies the composition of nuclear weapons, which typically contain fissile materials such as plutonium-239 or uranium-235. Over time, the stability of these isotopes is influenced by a myriad of factors. Radioactive decay and the age of the weapon component unequivocally contribute to the degradation of its effectiveness. With each passing year, structural integrity and the functionality of critical components may diminish, raising concerns about the reliability of a weapon that has not been tested over extended periods.

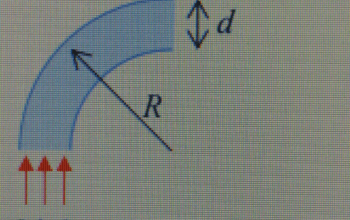

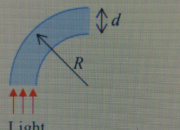

A pivotal concept in this discussion is the notion of ‘nuclear yield.’ The explosion produced by a nuclear weapon is contingent upon the efficient fission or fusion of the fissile material. This process necessitates precise engineering and meticulous assembly of various components, including tamper materials, reflectors, and neutron initiators. As components age, even minor inconsistencies can provoke catastrophic failures, which may manifest as reduced explosive yield—thus effectively rendering the weapon ‘bad.’ Furthermore, the phenomenon of ‘pit aging’—where the plutonium core degrades—has been a focal point for researchers examining whether aging impacts the efficacy and reliability of nuclear arsenals.

Moreover, the interplay between nuclear stewardship and the physical environment cannot be overlooked. Nuclear weapons are often stored in diverse geographical contexts, each with its unique environmental challenges, such as temperature fluctuations, humidity, and seismic activity. These factors can significantly impact the stability of both the materials and the weapon’s architecture. The potential for corrosion, chemical reactions, and material fatigue raises an important question: could a lack of proper maintenance or storage practices inadvertently render a strategic asset obsolete?

Technological advancements have also played a vital role in our understanding of nuclear weapon reliability. For example, the implementation of non-destructive testing methods allows experts to assess the structural integrity of weapons without the need for detonation. Such techniques have made it possible to identify stress points and potential failures, leading to proactive measures for remediation. However, this begs another question: can reliance on such technologies create an illusion of security, prompting complacency in both supervision and maintenance?

Another dimension that deserves attention is the ethical and strategic considerations surrounding aging nuclear arsenals. Nations equipped with older nuclear weapons may face pressure to either modernize their arsenal or confidently declare them as still operational and reliable. This dilemma emerges in the context of global disarmament efforts, where the desire for security must be balanced against the collateral effects of maintaining aging weapons. Once again, one must ask: does the act of preserving outdated nuclear weapons ultimately serve to exacerbate international tensions rather than mitigate them?

As we navigate through this labyrinth of uncertainty, it is critical to consider the geopolitical implications of nuclear weapons that may ‘go bad.’ If a nuclear state finds its arsenal compromised—be it through technological failure, material degradation, or inadequate maintenance—the ramifications could be profound. Nations may inadvertently be drawn into arms races, each seeking to secure its position by modernizing or expanding their arsenal in the face of perceived obsolescence. The potential for miscalculation increases exponentially, raising the specter of nuclear confrontation—a scenario fraught with peril not just for the involved parties, but for the global community.

At this juncture, it is essential to reflect upon the protocols surrounding the decommissioning of nuclear weapons. Disarmament initiatives, such as the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), aim to systematically dismantle outdated arsenals, yet the process is complex and rife with political contention. These treaties can serve to diminish the risks associated with nuclear weapons that have aged poorly. However, implementation can be hindered by national interests, trust deficits, and the fear of losing strategic advantages. This leads us to a thoughtful challenge—if a nuclear weapon is rendered unequivocally ‘bad,’ how does one ensure safe disposal while maintaining national security?

In conclusion, the question of whether nuclear weapons can ‘go bad’ invites a multifaceted exploration of scientific, technical, and philosophical considerations. The prospect of an aging nuclear arsenal, fraught with risks of failure and obsolescence, reveals a complex tapestry of challenges. As nations continue to grapple with these issues in the theater of global politics, the interplay between ethical stewardship and technical reliability becomes paramount. Ultimately, the effort to maintain a robust and secure nuclear arsenal will necessitate ongoing vigilance, innovation, and an unwavering commitment to the ideals of peace and security in a world beset by uncertainty.