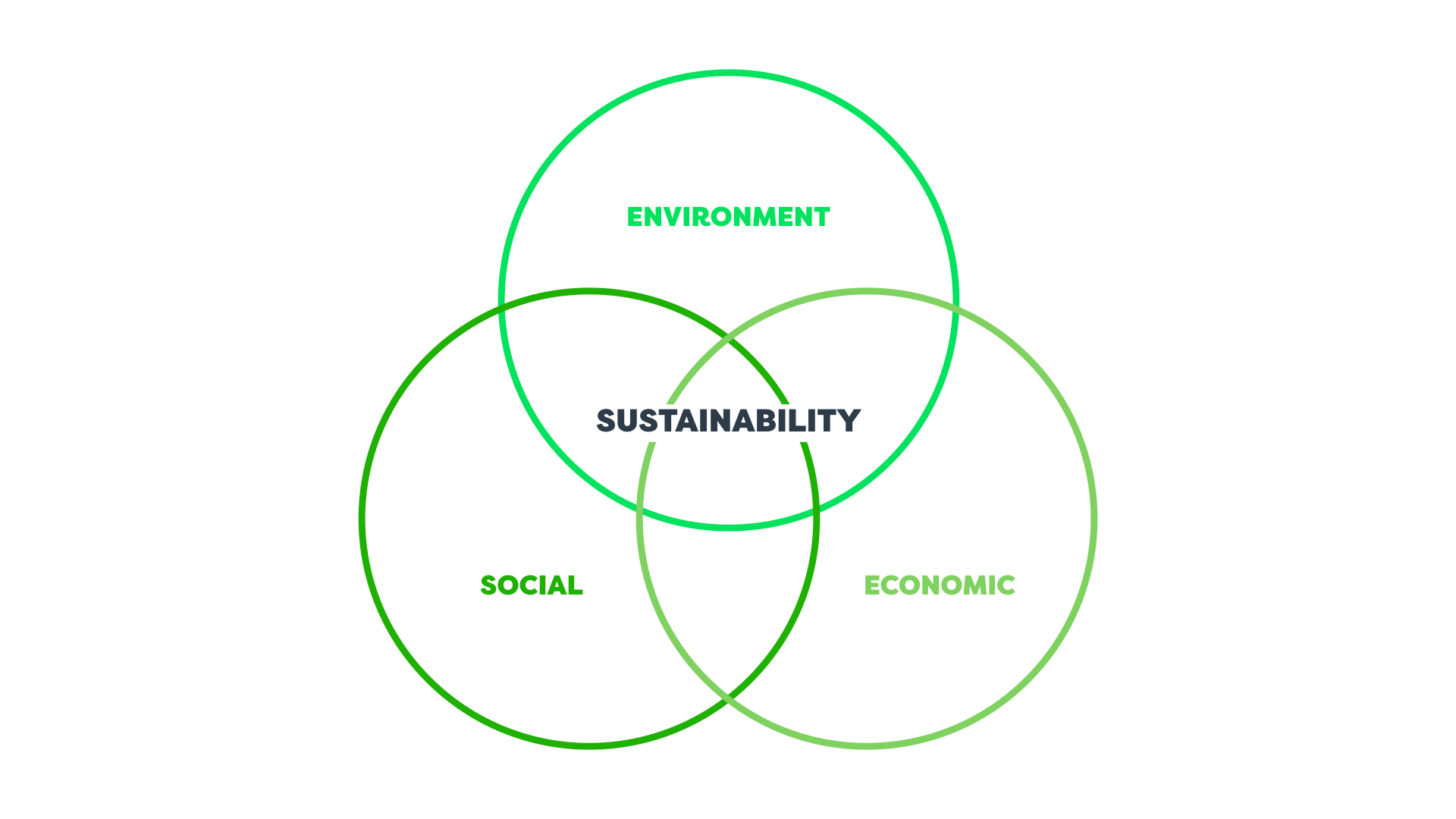

The concept of sustainability has emerged as a critical framework for understanding and addressing the multifaceted challenges facing humanity and the planet. The “three pillars of sustainability”—environmental, social, and economic—serve as a heuristic for balancing these interconnected facets. But where did these pillars originate, and what historical and theoretical underpinnings have shaped their development? This exploration delves into the origins of the three pillars of sustainability, tracing their evolution through a historical lens, examining the influence of various disciplines, and reflecting on their contemporary significance.

To comprehend the inception of the three pillars of sustainability, one must initially consider the broader educative and philosophical movements surrounding environmentalism and social justice that flourished throughout the 20th century. After World War II, a confluence of factors—industrialization, urbanization, and globalization—intensified the discourse surrounding environmental degradation and social inequality. These developments elicited an urgent desire for an integrated approach to policy-making, prompting scholars, scientists, and activists alike to seek a more holistic understanding of human interaction with the environment.

One of the pivotal moments in the discourse of sustainability can be traced back to the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, held in Stockholm, Sweden. This landmark event not only marked a growing global awareness of environmental issues but also demonstrated an increasing recognition that human well-being cannot be dissociated from the health of the planet. The ensuing release of the “Stockholm Declaration” articulated the necessity for sustainable development as an ethical imperative, emphasizing the need for harmony between environmental stewardship and socio-economic development.

The term “sustainable development” was formally crystallized in 1987 through the publication of the Brundtland Report, officially known as “Our Common Future.” Commissioned by the United Nations, this foundational document provided a comprehensive framework for understanding sustainability within the realms of environmental integrity, economic viability, and social equity. The Brundtland Commission underscored that true sustainability entails not only environmental protection but also the alleviation of poverty and the pursuit of economic growth that does not come at the expense of future generations. This integrative perspective laid the groundwork for the now-standard tripartite model of sustainability—an innovative conceptual framework that recognizes the necessity of addressing these three dimensions as inherently interconnected.

The environmental pillar, one of the cornerstones of sustainability, has its origins deeply ensconced in ecological theory and environmental ethics. The ecological paradigm emphasizes the intrinsic value of natural systems and organisms, positing that the environment possesses rights and merits moral consideration. Pioneering figures such as Rachel Carson, with her seminal work “Silent Spring,” challenged the prevailing anthropocentric notions of progress and prosperity, highlighting the deleterious effects of pesticides and pollution on both ecosystems and human health. This environmental advocacy spurred a burgeoning movement that sought to reconcile human activity with ecological resilience, leading to the emergence of conservation practices and environmental legislation.

In tandem with the environmental pillar, the social dimension of sustainability has its theoretical roots in social justice and human rights discourses. The understanding that equity and fairness must underpin development initiatives arose from various sociopolitical movements in the 20th century. Feminist theory, anti-colonial movements, and civil rights activism have all underscored the necessity of inclusivity and representation in policy decisions. This socio-centric approach to sustainability seeks to empower marginalized communities, promote equality, and assure that development benefits all members of society, thereby enhancing social cohesion and resilience.

The economic pillar, while occasionally viewed as a byproduct of traditional capitalist paradigms, has seen a transformation in its interpretation within the sustainability framework. A narrow focus on short-term profit maximization has been supplanted by a more holistic worldview that champions sustainable economic practices. It contemplates how economic systems can operate within ecological limits, advocating for a circular economy that emphasizes resource efficiency and waste minimization. The rise of social enterprises, green investments, and ethical commerce illustrates a broader recognition that economic activities should not only engender profit but also foster ecological health and social welfare.

As we scrutinize the historical trajectory of the three pillars of sustainability, it becomes evident that their development is emblematic of a more profound societal reckoning with the consequences of unchecked growth. The interlacing of environmental integrity, social equity, and economic viability mirrors a widespread yearning for a more equitable and sustainable future. Each pillar is interdependent, reinforcing the notion that prioritizing one dimension at the expense of others leads to inefficacious, if not detrimental, outcomes.

In contemporary discourse, the trio of sustainability pillars continues to evolve. Global challenges—such as climate change, social inequities, and economic instability—necessitate an adaptable framework that can respond to emerging realities. The burgeoning field of sustainable development fosters interdisciplinary collaboration, allowing for innovative solutions that transcend traditional sectoral boundaries. Furthermore, tools such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have catalyzed global cooperation, compelling nations to align their policies with principles of sustainability.

To conclude, the three pillars of sustainability represent more than mere conceptual models; they are rooted in a rich tapestry of historical developments, interdisciplinary dialogue, and ethical considerations. Their origins reflect humanity’s quest for balance amidst the complexities of modernization and environmental degradation. As engagement with these pillars deepens, a more nuanced understanding of their interconnections will likely advance the discourse surrounding sustainability, ultimately guiding policy and practice toward a more harmonious existence with the planet and each other.