The pursuit of knowledge within environmental research is both a pressing necessity and a multifaceted challenge. As ecological crises loom and the effects of climate change unfold at an unprecedented rate, the need to identify and comprehend existing gaps in research becomes paramount. These gaps not only represent areas where knowledge is insufficient but also illuminate underlying complexities and interdependencies that have yet to be fully articulated. This article scrutinizes various dimensions of gaps in environmental research, revealing nuanced intricacies that provoke both curiosity and concern.

One of the most conspicuous gaps in environmental research lies in the realm of interdisciplinary collaboration. Environmental issues inherently span multiple domains: ecology, sociology, economics, and political science, to name a few. Yet, academia frequently operates within silos, whereby researchers specialize in narrowly defined areas. This compartmentalization can lead to a dearth of comprehensive analyses that account for the multifaceted nature of environmental challenges. For instance, while studies may elucidate the ecological impacts of deforestation, they often neglect the socio-economic factors driving such practices. A more integrated approach—one that synthesizes insights from varied disciplines—could yield transformative understandings and innovative solutions.

Moreover, the temporal scope of research presents another significant gap. Much of the existing literature focuses on short-term environmental phenomena, such as seasonal changes or immediate human impacts. This myopic perspective often overlooks long-term trends, historical contexts, and evolutionary processes. The relationships between climate variables and species adaptation, for example, require longitudinal studies that span decades, if not centuries. By prioritizing a more expansive temporal framework, researchers might unveil critical patterns and leverage historical data to inform predictive models and contemporary policy-making.

Geographical biases also pervade environmental research, regularly skewing focus toward geographically privileged regions, typically in the Global North. These areas often dominate studies, while the Global South remains underrepresented. Such biases ignore the rich biodiversity and unique challenges present in developing nations. Consequently, solutions developed within specific contexts may not be universally applicable. Emphasizing comparative studies across different global regions could illuminate diverse ecological strategies and foster localized adaptations that resonate with various communities.

Another dimension requiring scrutiny is the insufficient exploration of non-human stakeholders in environmental research. While much emphasis has been placed on human impacts on ecosystems, the reciprocal effects between humans and non-human entities—such as animals, plants, and microorganisms—remain inadequately explored. The concept of eco-centrism calls for a paradigm shift where the intrinsic value of non-human life is recognized and studied. A flourishing ecosystem is predicated on the interdependencies among all its constituents. Researching these relations more profoundly could enhance conservation efforts and foster greater ecological resilience.

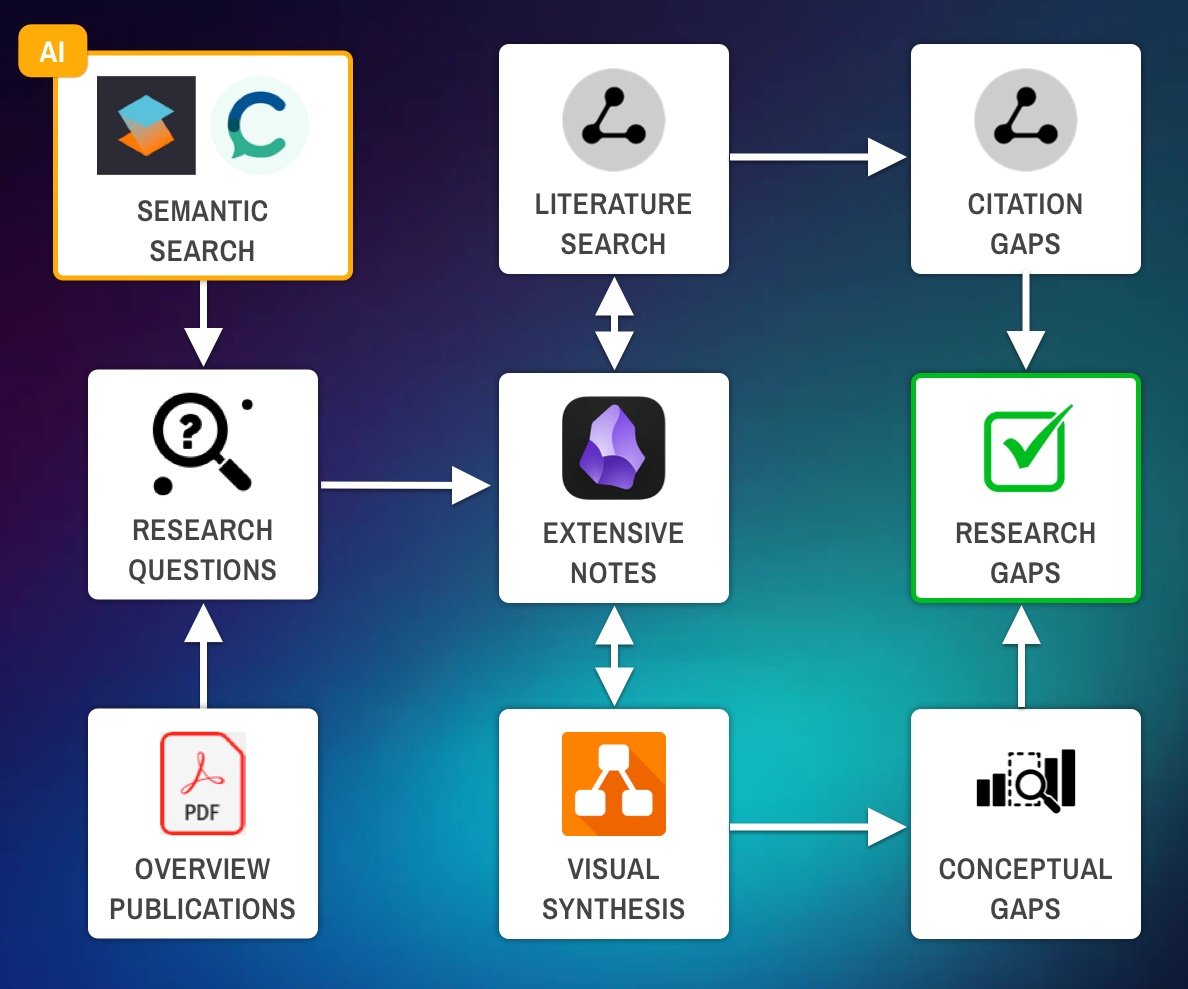

The adoption of emerging technologies and methodologies also exemplifies a significant gap in environmental research. Advanced tools, such as remote sensing and big data analytics, have the potential to revolutionize our understanding of environmental dynamics. Nevertheless, the integration of these technologies into traditional research methodologies has been sporadic. There exists a pressing need for researchers to embrace innovative approaches that harness the power of these tools while remaining grounded in empirical validation. As such, developing robust frameworks for emerging technologies can enhance our capacity to monitor environmental changes, predict outcomes, and assess the efficacy of interventions.

Compounding these gaps is the often-stymied translation of research into actionable policies. The existence of scientific knowledge does not guarantee its application in public policy or community practices. Bridging the chasm between research and policy implementation necessitates effective communication strategies that consider the diverse stakeholders involved—from governmental entities to local communities. Fostering dialogues where scientists and policymakers collaborate to co-create solutions can engender sustainable practices that resonate with both ecological integrity and social equity.

Lastly, the attitudes and values surrounding environmental stewardship warrant further investigation. Understanding the cognitive and cultural frameworks that shape human interactions with the natural world is crucial. What may be deemed as sustainable practices in one culture can be interpreted differently in another. Therefore, anthropological inquiries into the ethical perceptions of environmental responsibility can provide invaluable insights. These studies can elucidate the motivational factors that drive ecological behaviors, ultimately informing more effective environmental education and engagement strategies.

In conclusion, the gaps in environmental research reveal profound intricacies that extend far beyond mere knowledge deficits. Addressing these gaps demands a concerted effort to foster interdisciplinary collaboration, embrace innovative methodologies, and prioritize long-term perspectives. Furthermore, geographical inclusivity, a holistic view of ecosystems, and effective communication strategies are vital for translating research into practice. As the global community grapples with pressing environmental issues, recognizing and addressing these gaps can propel collective efforts towards a more sustainable and equitable future. By delving deeper into these multifaceted realms, environmental research can better inform and shape the policies and practices that will ultimately mitigate ecological degradation and promote environmental resilience.