The distinction between a tool and an instrument is a nuanced inquiry that engages both philosophical musings and practical considerations. At the core, both terms represent entities that facilitate human action, yet they engender different connotations and applications across various domains, from the arts to the sciences. To elucidate the intricacies of this discourse, this article will navigate through the etymological roots, contextual usages, and layered interpretations that encapsulate the essence of tools and instruments.

To commence, an etymological examination reveals that both “tool” and “instrument” trace back through linguistic history, offering insights into their divergent meanings. The term “tool” originates from the Old English “tol,” which denotes an implement applicable to labor or craft. In contrast, “instrument” derives from the Latin “instrumentum,” connoting a means or apparatus utilized for a specific function, often associated with more complex and nuanced undertakings. Thus, while a tool often implies a straightforward implement, an instrument tends to suggest an application imbued with precision and finesse, reflecting its ability to effectuate delicate or intricate tasks.

Contextualizing these terms within their practical realms serves to deepen our understanding of their unique respective functionalities. Tools, ranging from hammers and saws to more contemporary technological devices like software applications, are predominantly associated with manual labor and craftsmanship. They embody utility and are designed to manipulate physical materials, shaping them according to human intent. For instance, a carpenter wields a chisel not solely to carve wood, but to breathe life into raw material, transforming the banal into the beautifully functional.

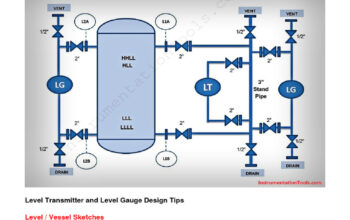

Conversely, instruments are frequently applied in specialized fields, whether in the arts, sciences, or even medicine. The essence of an instrument lies in its design to perform precise measurements or facilitate sophisticated processes. A musical instrument, such as a violin, serves as a conduit of artistic expression, channeling sound waves that evoke emotion and convey narrative. In the medical realm, instruments like a scalpel or stethoscope are not just tools but essential implements of diagnosis and healing, indicative of the delicate interplay between functionality and artistry in practice.

In exploring the artistic domain, the disparity between tools and instruments often accentuates the creative process. Visual artists may utilize various tools, such as brushes and palettes, to render their vision on canvas. Yet, the same artists may also engage instruments, such as software applications for digital art, that allow for a multifaceted exploration of form and color, resonating with intricacies of design and intention. In this context, the metaphoric juxtaposition signals that while tools may lay the groundwork of creation, instruments fill the gaps with nuance and depth, providing a transformative experience for both the creator and the audience.

This metaphorical elucidation extends into the realm of scientific inquiry. In an experimental setting, a technician may utilize tools, such as wrenches and soldering irons, to assemble apparatuses. However, the ultimate success of these endeavors often relies on the employed instruments like spectrometers or oscilloscopes that measure and analyze with precision. Herein lies the critical distinction—tools facilitate the construction, while instruments enable understanding. This hierarchy reinforces the idea that while tools may operate on a macro level, instruments engage with the micro, delving into the subtle intricacies of phenomena that elude casual observation.

Moreover, the philosophical implications of tools versus instruments evoke considerations of agency and intention. A tool is often perceived as an extension of human capability, manifesting agency through its use. It serves as a mere facilitator of action, whereas an instrument embodies a more reciprocal relationship; it necessitates user engagement and skill to unlock its potential. Here, the metaphor shifts toward the human experience—tools may reflect personal dexterity, but instruments reveal the depth of intellectual engagement and contextual understanding.

In a modern context, the blurring lines between tools and instruments further complicate the discourse. With the advent of technology, digital interfaces often oscillate between the definitions of traditional tools and instruments. Applications designed for productivity can serve as both—promoting efficiency while also requiring a certain level of expertise and nuance to navigate. The smartphone, for example, constitutes a multifaceted entity, providing users with tools for communication and instruments for artistic creation, effectively underlining the convergence of both functionalities.

Ultimately, the distinction between tools and instruments transcends mere semantic differences; it speaks to the very nature of human interaction with the world. Our tools allow us to shape, build, and manipulate our environment in immediate and tangible ways, while our instruments extend our understanding, fostering exploration and discovery. This intricate relationship between the concrete and the abstract reveals a profound truth: we are not merely users of tools or instruments; we are navigators of a continuum that fosters both creation and comprehension.

As we reflect on these insights, it becomes evident that both tools and instruments possess their unique appeal, threading together the practical and the philosophical. Just as a sculptor chisels stone with careful intent, or a scientist calibrates instruments in pursuit of knowledge, the duality of these concepts enriches our understanding of human ingenuity and creative expression. Whether tethered to the earth through labor or soaring into the ethereal through artistry, tools and instruments are forever interlinked, echoing the narrative of our endeavor to control, understand, and elevate our existence.