When pondering the fundamental nature of reality, one cannot help but inquire into the dimensions that comprise our universe. Specifically, one might pose the question: do true one-dimensional (1D) or two-dimensional (2D) objects exist within the cosmic tapestry? Such an inquiry challenges both philosophical paradigms and physical interpretations of dimensionality.

To dissect this question, it is essential to first delineate the concepts of dimension. In physical terms, dimensions are the degrees of freedom available to an object or a space. A one-dimensional object, for example, possesses only length, entirely lacking breadth and height. Conversely, a two-dimensional object incorporates both length and width, existing solely in a flat plane devoid of depth. In our three-dimensional reality, can we identify or conceive of entities that precisely epitomize the characteristics of 1D or 2D forms?

The realm of theoretical physics provides a fertile ground for exploring these dimensions. String theory, for instance, posits that the fundamental constituents of the universe are not point-like particles but rather one-dimensional “strings.” These vibrational entities elude direct observation, existing within multiple dimensions—most prominently in the higher-dimensional frameworks theorized by physicists. While the strings themselves can be categorically identified as 1D, their manifestation and interaction with the fabric of spacetime complicate our understanding of their dimensional integrity.

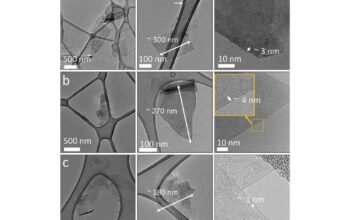

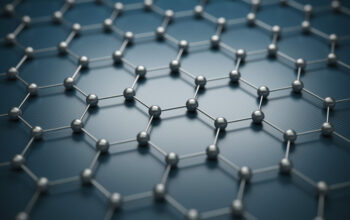

Moving to the realm of two-dimensionality, one might consider the concept of surfaces. Every physical surface—a tabletop, a sheet of paper, or the skin of an apple—serves as a tangible example of a 2D form. However, these surfaces are invariably embedded within a three-dimensional space, thus challenging their classification as purely two-dimensional entities. They always possess a certain thickness, however minuscule it may be, which veers them away from the ideal 2D representation.

One particularly intriguing instance of apparent 2D existence arises in the discussion of quantum mechanics and the phenomenon of wave functions. The notion of a wave function suffices to map the probabilities of finding a particle within a given area. In this regard, one could argue that wave functions represent a 2D spatial distribution of potential positions, set against the backdrop of a 3D universe. Yet these are not “objects” in a physical sense but rather mathematical constructs essential for interpreting quantum behavior.

Another fascinating aspect of dimensionality can be explored through the lens of abstract entities—such as mathematical points and lines. In a geometric context, a point can be considered a zero-dimensional object; it possesses no length, breadth, or height. A line, defined as an infinite collection of points arranged in a linear fashion, emerges as the quintessential representation of a 1D object. Nevertheless, while we can articulate and manipulate such concepts, their intangible nature challenges the identification of tangible 1D objects within the universe.

To further complicate matters, one must acknowledge the role of digital representations and simulations. As technology evolves, virtual environments often depict 2D spaces rendered on 3D screens. Pixels on a display can approximate 2D constructions, yet they are ultimately manifestations borne of electronic signals and not physical entities. Thus, this raises a new layer of inquiry: can one quantify the reality of dimensions when they exist in a synthetic context?

On a philosophical level, the discourse around 1D and 2D objects invites reflections on the nature of reality itself. The exploration of dimensions instigates an invitation to question our perceptual limitations and cognitive frameworks. Are 1D and 2D objects mere abstractions, remnants of our attempts to conceptually decipher the complexities of a multi-dimensional universe? If so, then their existence might be relegated to the realm of thought rather than actuality.

Consider also the implications of dimensional theories, such as those positing more than three spatial dimensions. If spacetime indeed possesses additional dimensions, the properties of 1D and 2D objects may shift dramatically. These hypothetical dimensions would alter our understanding of the fundamental nature of existence itself, prompting us to rethink the validity of our established models.

In conclusion, the question of whether real 1D or 2D objects exist in our universe remains a captivating and intricate query. While instances such as theoretical strings, wave functions, and mathematical constructs flirt with the definitions of dimensionality, they ultimately illuminate the challenges posed by a universe steeped in complexity. The interplay of abstraction and reality endures as a pivotal theme in both physics and philosophy, encapsulating the relentless pursuit of understanding the very fabric of existence. The exploration of these dimensions may yet reveal further layers of our reality, inviting an ongoing dialogue that transcends conventional categorization. Thus, one might whimsically reflect: do we merely inhabit a world of 3D limitations, or are we trailing the ephemeral traces of 1D and 2D wonders yet to be fully comprehended?