The notion of Earth being a two-dimensional entity often sparks significant debate across both scientific and philosophical landscapes. This conjecture typically arises from the simplifications made in various modeling practices, as well as from metaphorical interpretations of our spatial understanding. Henceforth, the exploration of whether the Earth can be perceived as 2D demands an intricate examination of intrinsic concepts such as dimensionality, perception, and the manifold frameworks within which we interpret our world.

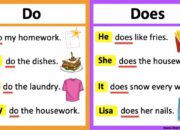

To initiate this discourse, it is imperative to delineate the essence of dimensionality. In general terms, dimensions can be understood as independent directions in which one can measure or navigate space. In the physical realm, three dimensions (length, width, and height) manifest the conventional understanding of spatial attributes. However, the theoretical frameworks of physics, particularly in relativity and string theory, hint at the possibility of additional dimensions that, while abstract, influence the fabric of reality.

Historically, cultural narratives and representations of Earth have oscillated between flat and spherical interpretations. Ancient civilizations often depicted the planet as flat due to limited observational capabilities, confined to localized experiences. This paradigm persisted until advancements in navigation and astronomy revealed the Earth’s true nature as an oblate spheroid. The transition to this spherical model underscores the evolution of scientific inquiry, emphasizing a shift from empirical deductions to theoretically robust understandings of celestial mechanics.

In the realm of philosophy, the inquiry into whether Earth can be deemed two-dimensional invokes contemplation about the nature of reality itself. Flat Earth theory, a contemporary manifestation of this inquiry, posits that our sensory perceptions, influenced by the immediate geographic context, lend themselves to misinterpretation. Advocates of this perspective argue that if the Earth were indeed a globe, the curvature should be palpably discernible in everyday life. This argument, however, neglects the profound implications of scale and perspective, fundamental concepts that frame our comprehension of the cosmos.

The distinction between two-dimensional representations and our three-dimensional reality can be illustrated through the lens of mapping. Maps, inherently two-dimensional, simplify the intricate topography of the Earth into flat forms. Cartographers navigate the dichotomy between dilation of scale and compression of detail, striving to maintain fidelity to geospatial relationships. This reductionist approach facilitates navigation and understanding but paradoxically engenders misconceptions about the Earth’s form. Notably, distortions in maps can skew perception related to size, distance, and spatial relationships, exemplifying the limitations inherent in two-dimensional portrayals.

Furthermore, exploring Earth’s dimensionality necessitates an examination of geometric foundations. Euclidean geometry, which predominates traditional interpretations, describes flat surfaces devoid of curvature. When discussing a seemingly flat Earth, adherents often cite Euclidean principles to bolster their assertions. Nevertheless, it is essential to recognize that non-Euclidean geometries—specifically Riemannian and hyperbolic geometries—introduce complexities that embrace curvature as a natural property of space. Thus, the elevation of a 2D perspective fails to account for the geometrical intricacies that dictate the nature of planetary bodies.

In relation to perceptual frameworks, cognitive constructs shape our understanding of reality. Cognitive psychology posits that our experiences and knowledge paradigms significantly influence our interpretation of the world. As such, one’s belief in a two-dimensional Earth may reflect underlying cognitive biases, nurtured by the proliferation of misinformation. This phenomenon is exacerbated by social media and digital platforms that facilitate echo chambers, where individuals receive validation for their perspectives, irrespective of empirical evidence. The resurgence of flat Earth beliefs in contemporary society serves as a compelling case study into human cognition and the malleability of belief systems.

It bears mentioning that scientific evidence overwhelmingly supports the spherical model of the Earth. Empirical observations, such as satellite imagery, patterns of celestial movement, and circumnavigation, substantiate this understanding. Just as notable are the physical phenomena that underscore the Earth’s curvature; for instance, the way maritime vessels appear to “sink” as they depart from shore, which reflects the curvature of the planet. Furthermore, the phenomenon of lunar eclipses, wherein the Earth casts a distinct round shadow on the moon, provides further validation of a spherical Earth.

Various scientific disciplines converge to reinforce the three-dimensional understanding of our planet. Geophysics elucidates the Earth’s geological formations and tectonic activities, while Earth sciences emphasize environmental interrelations that are inherently three-dimensional. The complexities of climate systems, atmospheric dynamics, and ecological interactions underscore the multifaceted nature of Earth’s existence that transcends simplistic two-dimensional categorizations.

In summation, while the intriguing proposition of a 2D Earth may foster engaging discussions within both scientific and philosophical terrains, the evidence and theoretical frameworks overwhelmingly advocate for an appreciation of its true three-dimensional form. The interplay between dimensionality, perception, and scientific inquiry invites meticulous examination, urging scholars to critique the emotional and cognitive underpinnings of our beliefs. Ultimately, the exploration of Earth’s dimensional nature enhances our grasp of not only our home planet but also the broader universe we inhabit, challenging us to question and expand the horizons of our understanding.